I gave up teaching English in Japan 25-years ago.

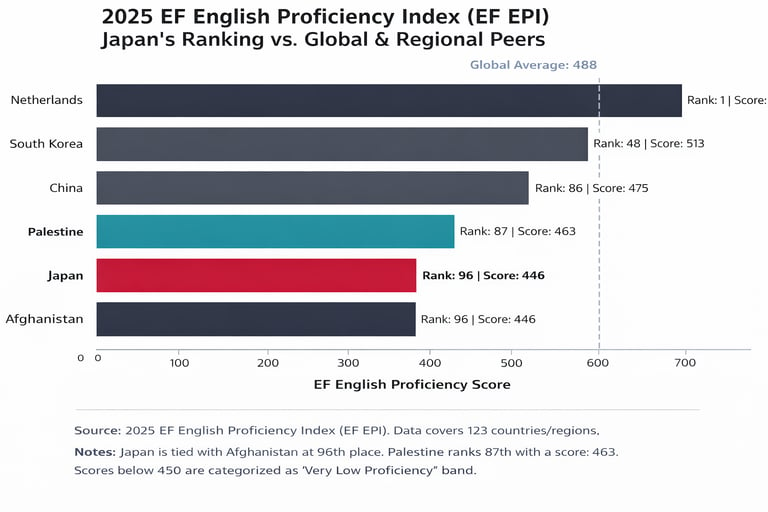

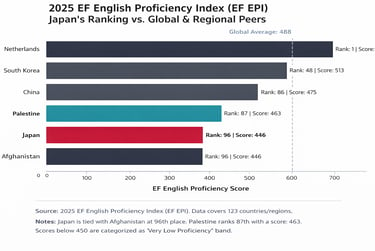

Let me be direct: Japan has spent decades building one of the world's most expensive monuments to educational futility. Students here study English for six years minimum—often ten or twelve when you count university—and the result? The 2025 EF English Proficiency Index ranked Japan 96th out of 123 countries, tied with Afghanistan. This marks the 11th consecutive year of decline. Japan scored 446 points against a global average of 488, placing it at the bottom of the "Low Proficiency" band. Japan finished 18th out of 25 Asian nations, behind China and South Korea. Let me tell you why I gave up.

1/21/20267 min read

This isn't about effort. Japanese students work harder than almost anyone. This is about a system designed to produce exactly what it produces: people who can parse grammar but can't order coffee in English.

The Test That Ate Everything

The university entrance exam system—juken—doesn't just influence English education. It is English education. Everything bends toward it. Teachers teach to it. Students memorize for it. Publishers design materials around it. The entire apparatus exists to sort students into universities, not to teach them a language.

Walk into most high schools and you'll find classes of 40 students focused on translation exercises, grammar drills, and reading comprehension of texts nobody would ever actually read. Speaking? That's not on the test. Listening to natural speech? Not tested either. The result is predictable: students who can explain the subjunctive mood but freeze when asked their name.

The skill breakdown from the 2024 EF EPI tells the story: Reading 454, Listening 437, Writing 394, Speaking 393. Students can read better than they can speak. That's the juken system working exactly as designed.

The Teacher Problem Nobody Mentions

Here's the uncomfortable truth: Japanese English teachers often can't speak English well themselves. Research from 2024 shows only 44.8% of middle school English teachers in Japan meet the CEFR B2 proficiency benchmark—the minimum standard for teaching a language. That means 55% of teachers fall below this threshold.

These teachers spent their careers learning English through the same failed system they now perpetuate. They learned grammar translation, not communication. Many pronounce English using katakana phonetics. They teach the test because that's all they know how to teach.

And here's the institutional trap: retraining hundreds of thousands of teachers who built careers around the current system is politically impossible. Admitting they lack the proficiency to teach effectively would require the entire system to acknowledge decades of failure. So instead, nothing changes.

When the Ministry of Education announced in 2013 that English would be taught in English, most teachers simply ignored it. They didn't have the language skills to comply. No consequences followed.

The data on classroom practice reveals the problem: 60% of instructional time goes to grammar and translation. 20% to reading comprehension. Only 15% to communicative activities. The policy says teach communication. The reality says teach grammar. The teachers can't bridge that gap because they were never trained to communicate themselves.

The Foreign Teacher Charade

Japan employs thousands of native English speakers through programs like JET. These are the people who actually speak English. So they must be teaching students to speak, right?

Wrong.

They're called Assistant Language Teachers for a reason. They assist. The Japanese teacher of English runs the class. The ALT stands in front of 40 students and becomes a human tape recorder. "Repeat after me." The students repeat. The ALT has no authority to change the curriculum, no input on pedagogy, no ability to focus on actual communication.

Many ALTs have no teaching training whatsoever. A bachelor's degree in any field qualifies you. The system doesn't want qualified teachers. It wants native speakers who will smile, pronounce words correctly, and not disrupt the grammar-translation method that dominates instruction.

And because ALTs are contract workers with no job security and lower pay than their Japanese counterparts, there's constant turnover. Students get a different native speaker every few years. No continuity. No relationship building. Just another accent to memorize.

The Class Size Problem

Try teaching conversation to 40 teenagers. Now try teaching conversation when 35 of those teenagers are too shy to speak, conditioned by years of education that punishes mistakes and values conformity over participation.

This is the reality of English education in Japan. Classes max out at 40 students by law—35 for elementary first graders as of 2021, with plans to extend the 35-student limit across all elementary grades by 2025, while secondary schools remain at 40. The average hovers around 38 students per class. Research shows optimal language learning happens in groups of 6-10 students. Japan's classes are four times that size.

In a class of 40 students studying English, maybe 5-6 are genuinely engaged language learners. The rest are marking time until the next exam. The teacher can't provide individual attention. Shy students disappear into the back of the room. The noise level makes meaningful group work impossible.

You can't teach people to speak a language in groups of 40. You can teach them to memorize grammar rules. You can prepare them for multiple-choice tests. But you cannot teach communication at that scale. The system knows this. The system doesn't care.

The Institutional Concrete

Here's what nobody wants to admit: the people running this system know it doesn't work. They've known for years. The Ministry of Education has announced reforms repeatedly. In 2002, they introduced communicative language teaching. In 2013, they declared English would be taught in English. In 2020, elementary school English became mandatory. In 2021, they expanded the 35-student class size limit in elementary schools.

And nothing changed.

Because changing the tests would disrupt the sorting mechanism that universities depend on. Changing teaching methods would require retraining hundreds of thousands of teachers who spent their careers mastering the current approach. Reducing class sizes would require hiring more teachers. Admitting the system failed would mean admitting that generations of students were failed.

So instead, there are announcements. Pilot programs. White papers. The machinery continues exactly as before. The 2025 rankings show the results: 11 consecutive years of decline. Japan's score hasn't risen two years in a row since the index began in 2011.

The Graduate Test

Try this experiment: approach any university graduate under 40—someone who studied English through the reformed curriculum, who had native English teaching assistants, who learned in schools with conversation lounges and multimedia labs. Ask them to describe their job. Ask them about their weekend. Ask them anything.

Most can't do it. They'll apologize, laugh nervously, say their English is poor despite studying it for over a decade. This isn't anecdotal failure. This is systematic success at the wrong goal.

I've tested this myself. Walk through Shibuya, Shinjuku, anywhere in Tokyo. Ask random university graduates simple questions. Watch them struggle despite perfect test scores and years of supposed English education.

The system produces exactly what it's designed to produce: people who can pass exams but cannot communicate.

What Actually Works

Other countries figured this out. The Netherlands ranks first in non-native English proficiency. They don't teach English as an academic subject to be studied. They use it as a medium. Their students watch shows in English, take university classes in English, communicate in English from early ages.

South Korea was once comparable to Japan. Then they invested in teacher retraining, conversation-focused curricula, and changed university entrance requirements. South Korea now ranks 48th globally—48 spots ahead of Japan.

The Philippines ranks 22nd. Malaysia ranks 24th. Both use English as a working language in education and government. Singapore, previously ranked 3rd before being reclassified as a native English-speaking country in 2025, made English the language of instruction across its education system.

Even China, with a population 10 times larger and far more linguistic diversity, ranks 86th—10 spots ahead of Japan. China reformed its English education in the 1990s and 2000s, emphasizing practical communication skills and hiring qualified teachers.

The pattern is clear: proficiency comes from use, not study. Countries that treat English as a tool for communication produce speakers. Countries that treat it as an academic subject produce test-takers who can't speak.

The Cost of Inertia

Japan is paying for this failure in ways that compound. Companies struggle to globalize because their workforce can't communicate internationally. Rakuten mandated English as its corporate language in 2010. Most employees still can't use it effectively. Fast Retailing (Uniqlo) tried the same. Same results.

Universities drop in global rankings partly because they can't attract international students or faculty. Why study at a Japanese university when instruction is in Japanese and nobody speaks English? Why teach there when you can't communicate with colleagues?

Young people who want international careers have to remediate their English education privately. Language schools are everywhere. Eikaiwa chains employ thousands. Millions of yen flow through an industry that exists solely to fix what schools failed to teach. It's a tax on ambition.

And here's the economic reality: Japan needs immigrants. The population is shrinking. The birth rate is catastrophic. The workforce is aging. Foreign workers are essential. But those workers need to communicate. When the local population can't speak the international language of business, integration fails.

The 2025 EF EPI noted something else: motivation is declining. When people see no real-world benefit to English, they stop trying. Why spend years studying a language you'll never use? Why put in effort when the system doesn't value actual communication?

Japan's English education isn't just failing. It's failing more every year.

The Billion-Dollar Industry of Failure

Meanwhile, English teaching is a massive industry. Private language schools, test preparation, textbook publishing—the JET program alone has an annual budget exceeding ¥45 billion (approximately $314 million USD) for over 5,000 participants. That's roughly $63,000 per participant when you factor in all program administration costs, training, and support.

Add private eikaiwa schools. Add test prep. Add textbooks. Add the thousands of ALTs employed by dispatch companies at low wages. The total economic activity around English education in Japan likely exceeds $10 billion annually.

And for what? Eleven consecutive years of declining proficiency. Scores that never rise two years in a row. Rankings at the bottom of Asia. Graduates who apologize for their English after a decade of study.

It's beautifully inefficient. A perfect closed system where everyone gets paid, nobody succeeds, and the failure perpetuates itself.

The Hard Truth

This system will not reform itself. It cannot. Too many people are invested in its continuation. Too many institutions would have to admit error. Too much money flows through maintaining the status quo. Too many teachers would need to be retrained or replaced. Too many universities would need to redesign entrance exams.

So Japan will continue ranking at the bottom of English proficiency indices. Graduates will continue apologizing for their English after 12 years of study. Ministers will continue announcing reforms that don't reform anything. Companies will continue struggling to find employees who can work internationally. Young people will continue paying privately to fix what schools failed to teach.

Unless someone decides that actually teaching English matters more than maintaining the system that fails to teach it.

That would require treating the problem like it's actually a problem. Not a cultural inevitability. Not something to be reformed around the edges. A fundamental failure that requires fundamental change.

It would require:

Reducing class sizes to functional levels for language learning

Retraining or replacing teachers who lack language proficiency

Eliminating grammar-translation methods in favor of communication-focused instruction

Changing university entrance exams to test speaking and listening

Treating native English speakers as actual teachers with authority and training, not human tape recorders

Using English as a medium of instruction for some subjects, not just a subject itself

Measuring success by communication ability, not test scores

The question isn't whether Japan can fix this. The question is whether it wants to badly enough to disrupt the systems that make fixing it difficult.

Right now, the answer is clearly no. And every year, the ranking drops further.