The Project Nobody Wants to Share

When your student refuses to share their final project with anyone, they're not being shy. They're telling you it's worthless. Here's how to stop assigning work that students are ashamed of—and start building things that actually matter.

12/17/20253 min read

The Project Nobody Wants to Share

A student just told me she doesn't want to share her final project with anyone.

Not on social media. Not with friends. Not with the world.

I asked her why she was doing it then.

She had no answer. Because there isn't one.

Here's what we've built: an education system where students spend months creating things they wouldn't show to a single person who isn't required to look at it. We've normalized the production of work so meaningless that its creator recoils at the thought of anyone seeing it voluntarily.

This isn't about social media. It's about intention.

When you build something real—something that matters to you—you can't wait to show people. You want feedback. You want it to exist in the world. Even if you're scared, even if you're uncertain, there's a pull toward sharing because the work means something.

When a student actively refuses to share, they're telling you the truth: this project has no connection to their actual life.

So here's what changes:

Start with the audience first. Before assigning any project, identify who will actually benefit from it. Not "the teacher" or "the rubric." Real people. A local business that needs a solution. Younger students who need tutoring materials. A community organization that needs research. Elderly neighbors who need technology help. If you can't name a real audience who would miss this work if it didn't exist, don't assign it.

Let students choose their stakes. Some will want to publish on Medium. Others will present to city council. Some will share with ten people in their community. The size doesn't matter—the reality does. But "no one" isn't an option anymore. If they can't identify a single person outside the classroom who would care, they need a different project.

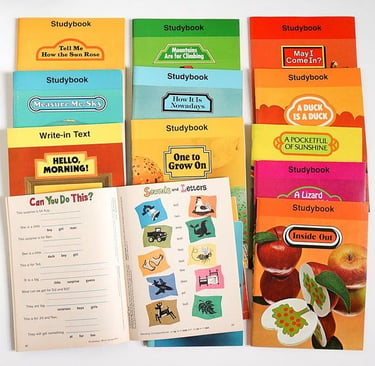

Replace fake projects with real ones. Stop assigning "practice" businesses, mock proposals, and simulated scenarios. A student analyzing their neighborhood's transportation problems and presenting findings to the transit authority learns more than one writing a fake business plan for a fake company. The research skills are identical. The motivation isn't.

Make "I don't know what to do" a valid starting point. Spend the first week of any project having students identify actual problems they see, questions they have, or things they wish existed. Interview five people about what frustrates them. Document three broken things in their community. Find two topics where experts disagree and they want to understand why. Real projects emerge from real curiosity.

Ship before it's perfect. Students won't share because they've learned that school work must be polished, complete, and graded before it's valid. Wrong. Publish the first draft. Get feedback. Iterate. Show them that real work gets better through exposure, not isolation. A blog post with three readers and two comments teaches more about communication than a perfect essay read by nobody.

Count impact as part of the grade. Did someone use what you made? Did you get questions? Did someone disagree with you? Did your work make something better, even slightly? These aren't soft metrics—they're proof the work was real. A video tutorial that helped four people is worth more than a presentation that impressed only the teacher.

Let them kill projects that don't matter. Halfway through, if a student realizes nobody actually needs what they're making, let them stop and start something else. In the real world, you abandon bad ideas. School should teach that discernment, not train students to finish meaningless work because they started it.

The test is simple: Will this exist after the grade is entered?

If the answer is no, you're teaching students that work is something to escape, not something to be proud of.

If the answer is yes, you're teaching them that their effort can change something real.

One creates graduates who've learned to endure pointless tasks.

The other creates people who know how to make things that matter.

Your choice.